/fəˈvelə/ noun |

a poor area in or near a Brazilian city, with many small houses that are close together and in bad condition

a robust plant prevalent in the Canudos hills in the northeast of Brazil

—————

It is nearly 17 years since I first visited a favela. And whilst time has softened the edges of my memories, three things jump to the forefront of my mind:

Gunshots, fireworks, and streets which we were forbidden to walk down.

For most European backpackers, gang warfare is a distant concept; a way of life glamourised by Hollywood for our entertainment rather than our concern. Movies such as ‘City of God’ (the spectacular film by Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund) should terrify us; instead they often excite those that travel to Brazil.

Which is exactly why so many of us don’t think twice about taking a favela tour, to walk the streets as voyeurs and tourists, guided by men that choose to show these neighbourhoods in their worst possible light. Indeed, my own experience was tantamount to a human safari, with stories that began and ended with violence, and without human connection, understanding or empathy.

Regrettably, I was simply too naive to realise what my brief visit to a neighbourhood which snaked its way up the hills meant for those that called the favela home. What it represented - and that by engaging in and funding an experience that only sought to confirm negative stereotypes to outsiders rather than educate, the vicious cycle went on.

Ethical and responsible travel was not a concept I was really aware of back in 2005. Indeed at age 21, I was a long way from realising that my actions could have an impact. I researched little (although it was a more difficult back then) and didn’t fully appreciate that travelling really should be more the just an acquisition of anecdotes and good times to impress people back home.

However, even then, that favela ‘experience’ never sat right with me and it’s something I’ve often thought back to when considering how much my travel awareness has changed in the intervening years.

When we returned Rio de Janeiro for the third time in late 2018 (still haven’t written a proper guide, sorry!), at the start of our four-month trip through South America, G Adventures invited us to join their new tour of the Vidigal favela. Run by Favela Experience, and supported by the Planeterra Foundation, this small grassroots project aim is to support those trying to provide options and alternatives for favela residents, a community of young and old, and to transform favela tourism into a positive community-led activity.

Importantly, it allows those from Vidigal to tell their own stories to visitors - free from the prejudice so often associated with those that call the favelas home.

People from the community like Russo, our enigmatic tour guide nicknamed the ‘Russian’ by friends since childhood due to his pale complexion. Having lived in Vidigal all of his life, it was the early days of favela tours that led him to turn to tourism and to do it in a way that was better for his neighbourhood.

“I saw people leading tours around my community, people who were not from here. I thought that if they could do it, so could I.”

And so he did.

For years now, he has been leading groups through the streets, and he now appears to be one of the most well-known people in the entire favela. Every street corner, shop, and group of men we pass, people shout out to him; there is no suspicion as to our presence, just apparent pleasure that we have come here to be shown around by a man from here.

Our first stop on the walking tour is to a colourful concrete football pitch which doubles up as a practice area for the local percussion group, Batuca Vidi. Run by Isis, an impressive young woman who has battled adversity to become a leader in the community, Batuca Vidi aims to use music as a way to teach discipline, dedication and structure to young local children that may otherwise fall victim to the gangs who operate in the vacuum that poverty creates.

We watch the kids, some struggling under the weight of their own bass drum, perform several impressive samba renditions accompanied by a well-timed bark or two from the street dog which has become their mascot.

A few teenage boys - no more than 13 years old - peer in from the door as the band members teach our small group some of the basics on the drums; I hope that the sight of kids from their own streets teaching us how to do something makes them curious to come back again.

We move on, following faithfully behind Russo as he gives us stories from his youth and points out his old home and local haunts, before our next stop: Vidigal Sitiê Eco Park, a garden created by the community and for the community through the removal of five tonnes of trash (there’s a lot of trash all over the favela). Until we reach it, the fact that there is so little green space or sense of nature, of anything that isn’t red brick, concrete or sheet metal, doesn’t really register. This Eco Park however - though nothing too remarkable on its own - strikes us as symbolic of something deeper, of the necessity for development to come not just in the form bricks and mortar.

Moving downhill towards the entrance of the favela, we visit Vidigal Capoeira, a community organisation founded eight years ago where they teach the famous Afro-Brazilian form of dancing martial art; more people keen to tell us, to show us, ways in which tourism done correctly can benefit communities socially and economically.

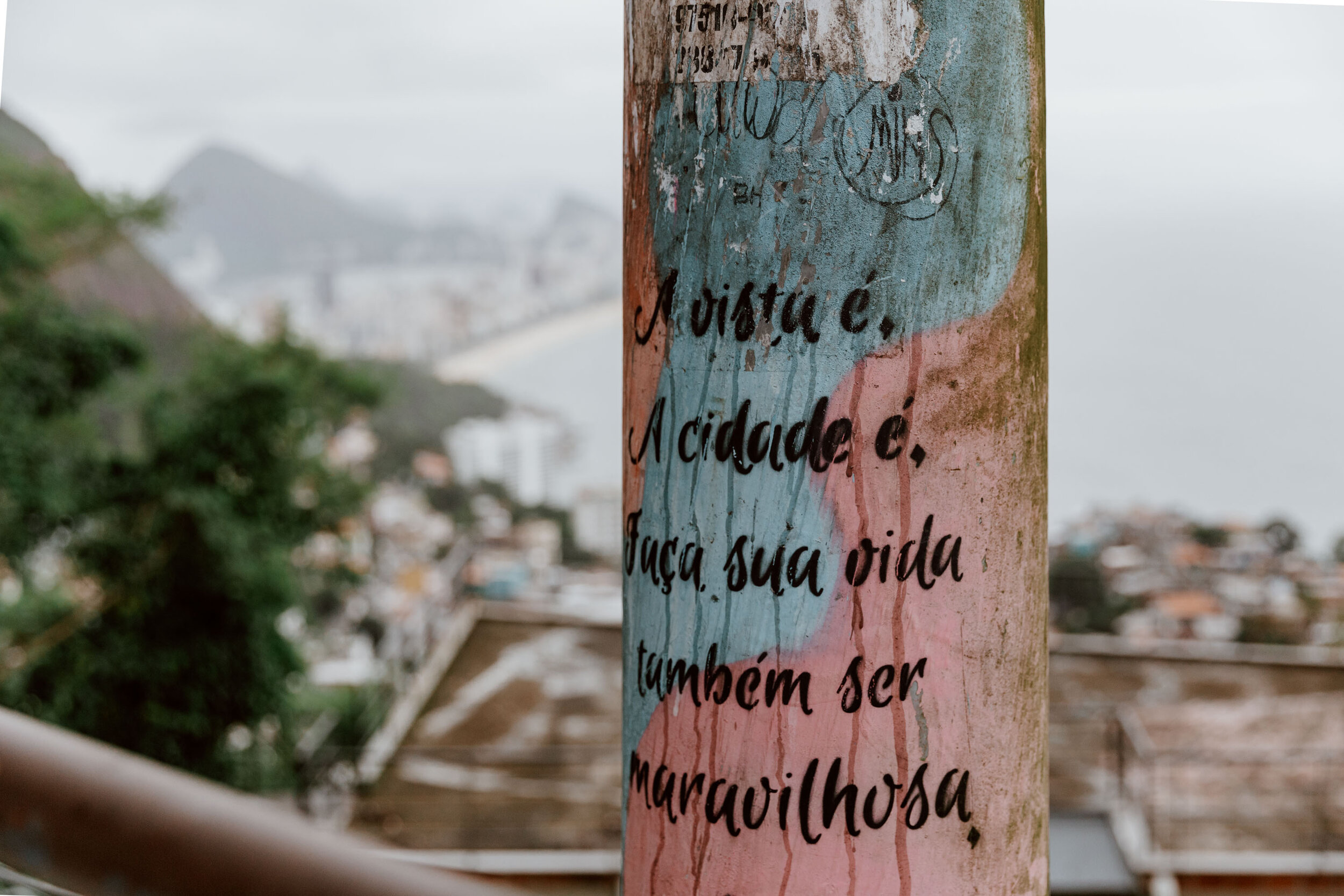

Our walk ended at Vidigal Beer, a microbrewery run by Luciano and his wife Nilda, and the first of its kind in the favela. Supported by the Planeterra foundation, their passion for craft ale now provides an income, a viable future - and a delightful way to toast to the end of our time in Vidigal, gazing out over the spectacular views of Ipanema Beach, and the Rio beyond.

The situation for people living in Vidigal and many of Rio’s other favelas may have changed slowly or not at all since my naive visit 17 years ago; according to a variety of statistics, it’s actually got worse.

There’s little point in glamourising or trivialising the struggles many will have faced, and succumbed to, in that period of time. Or to pretend that systemic issues will not remain for many of these communities, for which tourism at the edges cannot be a panacea. Or that all favelas in Rio will be able to undertake the same journey. However, my main takeaway from this visit on a grey day in Rio is that a renewed and more widespread awareness of the positive impact that responsible tourism can have - and needs to have - in supporting communities and change-makers like Isis and Luciano, is essential.

It’s our responsibility to help.